Maxine Cuffe, CFA, Vice President & Director of Global Strategies

mcuffe@haverfordquality.com

Tim Hoyle, CFA, Chief Investment Officer

thoyle@haverfordquality.com

As Covid-19 restrictions are rolled back across the country, businesses are facing another crisis: a shortage of available workers. “Help Wanted” signs are everywhere. McDonalds is offering a sign-on bonus. Taco Bell is doing “drive through” interviews. At Lowe’s, you can get interviewed and hired on the spot. The jobs market has rarely been this hot. Yet the country still has more than 9 million people searching for work. The economy is grappling with high unemployment and labor shortages at the same time.

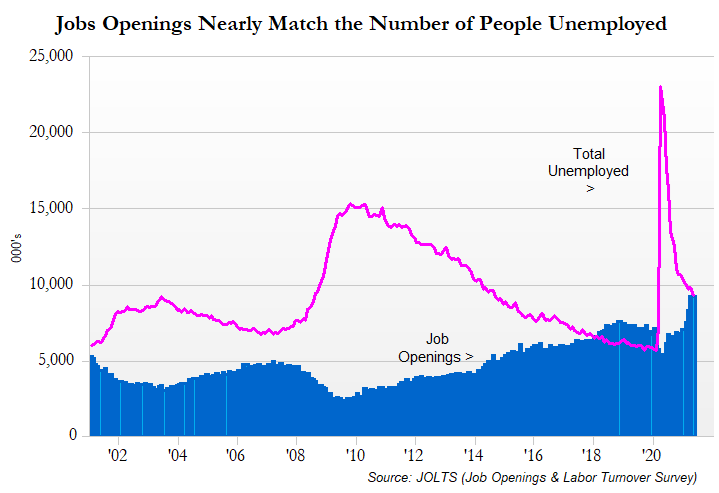

Data in recent weeks has shown more available jobs than unemployed workers. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ JOLTS survey, job openings hit an all-time high in April at 9.3 million unfilled jobs. That’s up more than one million jobs from the March data and represents nearly 6% of all jobs in the country. The survey also shows a record number of workers are quitting their jobs, seemingly for new ones at higher pay.

Yet millions of unemployed Americans are not looking for jobs, for a variety of reasons. The lack of reliable childcare has been an issue with hybrid school schedules, and, now that it’s summer, we see summer camps cutting capacity due to staff shortages. Lingering fears over Covid-19 are also holding back workers, even with vaccines becoming more widely available. Enhanced unemployment benefits are clearly having an impact, too. Some of this stems from the quality of the jobs on offer. Much of the job gains over the past six months have been in what we’d call low quality jobs: below average pay and/or less than full time hours. A part-time position at $11 an hour, the current average wage for food service workers, offers little incentive for someone receiving full-time Unemployment Insurance (UI) and an extra $300 per week Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation. The end of enhanced UI benefits should spur more interests in job openings in the months ahead. Already 26 states have announced the extra payment will end before the official end date of September 6th.

However, the country still faces a true labor shortage. Even before the pandemic, many companies were highlighting difficulties in finding staff with the right skills. Given current trends, shortages for engineers, IT professionals, and skilled tradespeople like electricians and carpenters are only going to get worse. Meanwhile, the pool of available workers has actually shrunk with more than 4 million people leaving the workforce during the pandemic. Many of these workers decided to retire early, not wanting to work from home or risk getting sick at their workplace. Covid-19 has had an unprecedented impact on immigration levels as well because foreign workers were unable to travel to take positions in the United States.

Does all this mean that workers can name their price? If you were only listening to the media, one would think that soaring wages are starting to pose a risk to the economic recovery through the dreaded price-wage spiral. But despite the headlines, the average worker’s pay doesn’t appear to be rising much faster than before the pandemic. According to the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker, wages are growing at just over 3% YoY, roughly in line with the average over the past five years. Workers in the bottom quartile and the youngest age groups are seeing better wage growth, offset by lower growth for older workers and those in the highest income brackets. This is a potentially Goldilocks scenario which puts more spending money in people’s pockets at the lower end but stops short of putting pressure on corporate profit margins.

Meanwhile hiring is picking up. The economy added 559,000 jobs in May, below economists’ forecasts, but still one of the best monthly gains of the past 30 years. This is all great news if you are a teenager. With little experience, teenagers are less picky than most workers and happy to take on part-time hours. Teenage unemployment fell to a 70-year low in recent months.

Shortployment doesn’t quite role off the tongue like stagflation, and hopefully it never will. Current levels of high unemployment and labor shortage is the result of an economic shock and a step-up in the wage demanded for many low-skilled jobs. This will result in higher prices, and likely higher wages up the income scale, but it is occurring alongside unprecedented consumer demand. We believe economic growth is poised to continue and optimistic consumers will continue to spend. Revenues will continue to grow helping to offset wage pressures and most companies should be able to adapt and thrive. Those companies that can’t will likely become the victim of creative destruction – replaced by new ones better tooled to thrive in the current environment.