Maxine Cuffe, CFA, Vice President & Director of Global Strategies

mcuffe@haverfordquality.com

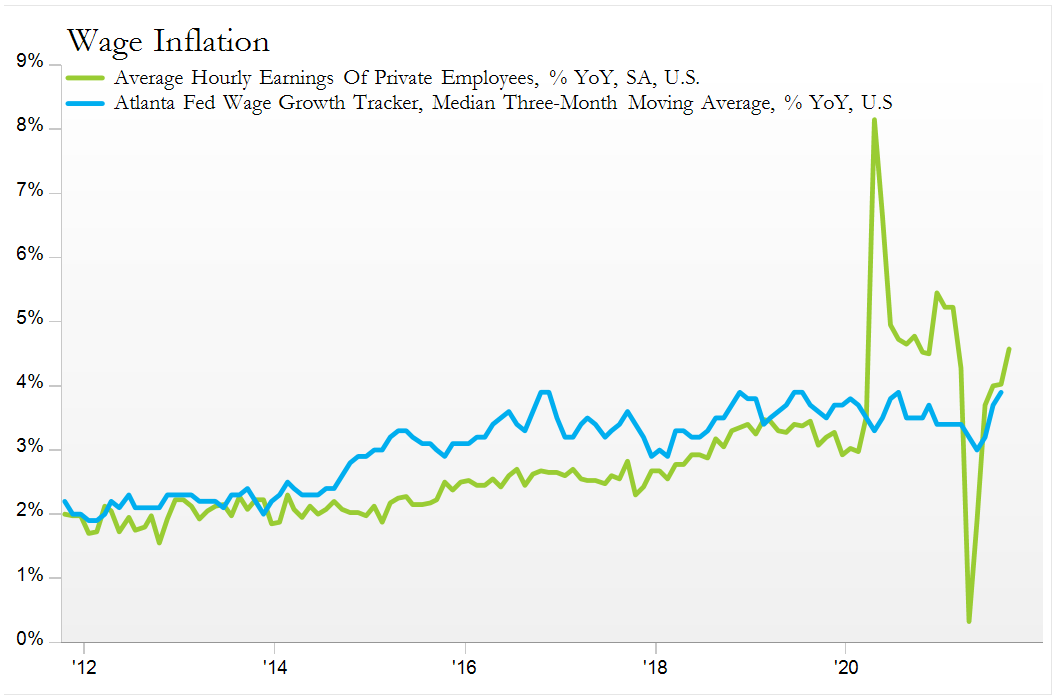

An alternative measure of wage inflation shows growth has been near 4% for the past 4 years

On the surface, last week’s non-farm payrolls number was a disappointment. The economy added just 194,000 jobs during the month, far below the expectation of 500,000, and the softest monthly data since December of last year. But as with all things these days, there are unusual circumstances that are distorting the figures. Usually, back-to-school season boosts the September job report, but this year educational jobs actually fell. Workers that lost jobs as a result of school closures during the pandemic, such as daycare staff and school bus drivers, have moved on to find new roles, creating a shortage of available workers now that schools are returning to normal.

The jobs report serves as a key indicator on the current state of the economy, and investors watch closely for implications for Federal Reserve policy. However, we don’t believe this weak report will deter the Fed from its plan to reduce monetary support in the months ahead. We fully expect the Fed will begin to taper its asset purchase program by the end of the year.

Upward pressure on wages is one area of concern that is pushing the Fed to taper sooner rather than later. The latest report from the Bureau of Labor indicated that wages grew 4.6% year-over-year (YOY) in September, increasing from a 4% pace the previous month. Again, this data has experienced unusual fluctuations over the past 18 months. Average Hourly Earnings are easily distorted when you remove millions of lower paying jobs from the calculation, as happened during the initial months of Covid-19. To get an alternative view, we look at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Wage Growth Tracker. This dataset measures workers’ salaries today, compared to the same individuals 12 months ago, and then reports the median growth rate of all workers. That figure hit 3.9% last month, the highest figure of the past decade. This gives us a clearer picture of the real underlying changes in the labor market, across all income levels.

Wage pressures are likely to persist, adding risks to the “transitory” inflation narrative. Businesses want to hire, but they can’t find enough workers to fill record job openings. And the size of the U.S. labor force continues to shrink. Since March 2020, more than 5 million people have exited the work force entirely. This includes workers that retired early, people with health concerns, and parents without childcare. Perhaps even vaccine mandates are holding people back from returning to work.

The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment, but there is a tension in achieving both of these in the age of Covid. Low worker participation is not ideal for the economy. But, if wages continue to accelerate, risking a wage-price spiral, the Fed’s hand will be forced into rising interest rates sooner than expected.